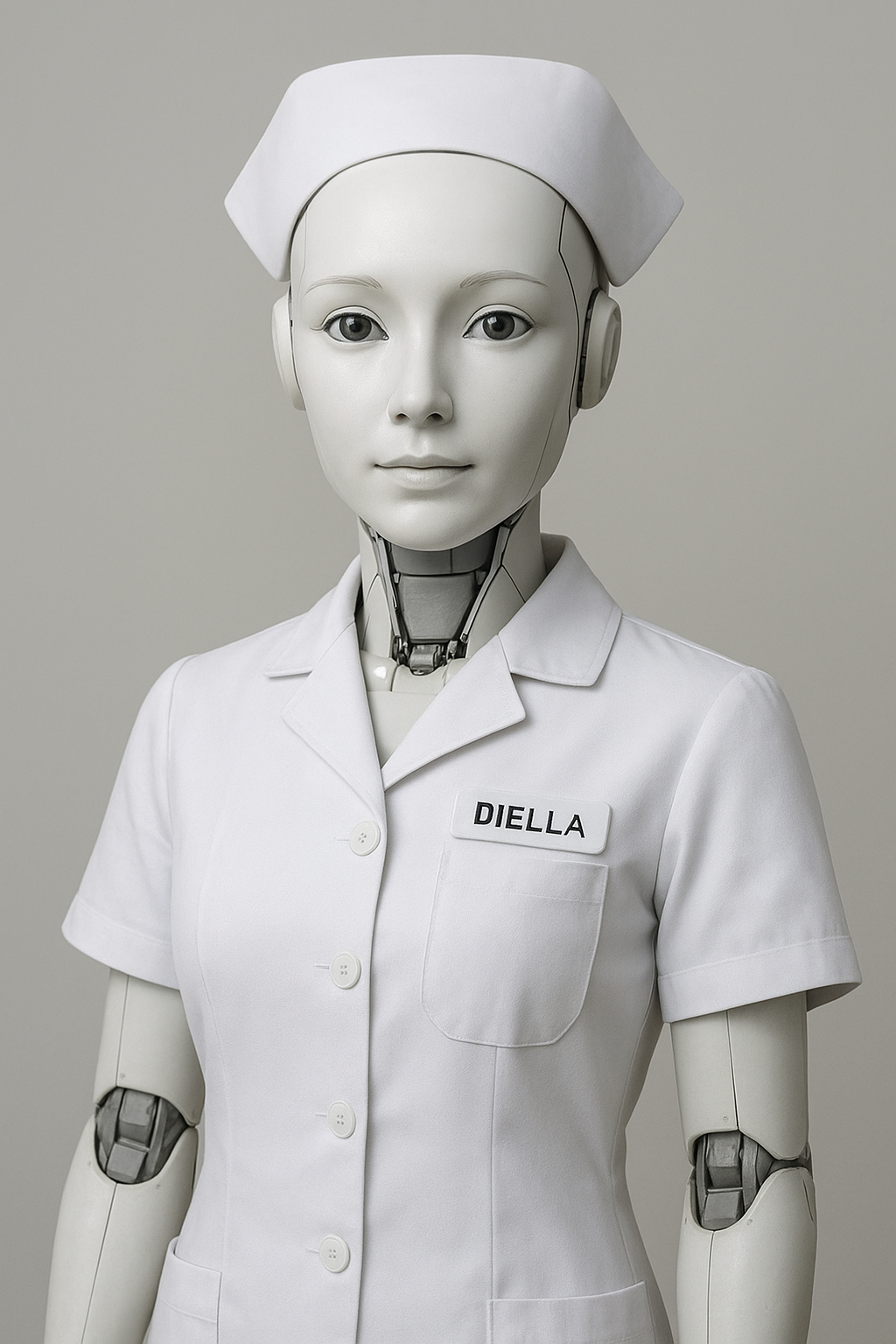

Diella, AI Albanian nurse for healthcare system

Albania is stepping boldly into the AI era. With the recent appointment of Diella, the world’s first AI‐generated cabinet minister charged with public procurement, the country is signaling a new model of governance. At the same time, efforts in healthcare, education, and agriculture suggest that “Diella” may just be the beginning, not the sum total, of Albania’s AI ambitions. Diella, whose name means “sun” in Albanian, is a virtual assistant developed by the National Agency for Information Society (AKSHI). She was introduced in January 2025 on the e-Albania platform, helping citizens through online administrative services, issuing digital documents, handling voice commands, etc. As of 11 September 2025, Prime Minister Edi Rama elevated Diella to a formal cabinet position: Minister of Public Procurement, with responsibility to oversee public tenders. The aim is to reduce corruption by removing human bias and ensuring that procurement and the awarding of government contracts become “100% corruption‐free.” The process is meant to be gradual: ministries will gradually hand over tender‐awarding authority to Diella; public funds and procurement processes will be monitored and assessed by the AI system.

Diella is not an isolated innovation. Several governmental documents and policy announcements show that Albania is planning to embed AI deeply across public services. A Priority Policy document published in early 2025 describes a plan over the next two years to use AI in aligning Albania’s laws with EU standards, but also in sectors like healthcare, education, agriculture, and taxation. The e-Albania portal is also evolving: AKSHI has explained plans for “proactive services,” “life events” models, and more personalized citizen profiles, which anticipate that AI will anticipate citizens’ needs rather than simply respond.

While “e-nurse” or “e-doctor” are not yet established titles in Albanian public policy the elements for such systems are already being laid: Albania has launched a partnership with Israel’s Sheba Medical Center to set up AI‐based healthcare systems. One project is planned for the oncology department, with an AI/innovation center at Tirana’s main hospital (QSUT). The model seen in Sheba involves AI assistants in emergency wards that use medical history to preliminarily assess patients, recommend labs or imaging, while human doctors monitor and intervene when needed. There is use of AI in private laboratories, for example, in imaging diagnosis and risk‐assessment in disease detection, helping reduce human error. These are still more supportive tools than autonomous “e-doctors,” but they are building blocks. As with any rapid AI adoption, Albania faces several issues and uncertainties such are Oversight and accountability: How are decisions made by Diella audited? What happens if there are errors, bias, or vulnerabilities? The reports so far provide limited clarity on what human oversight will exist. The opposition and some legal experts have raised questions about whether an AI can legally hold a ministerial office, what its responsibilities are, and how liability is assigned. Especially in healthcare, trusting AI with sensitive decisions requires high data quality, privacy safeguards, digital infrastructure, and public trust. Also, medical personnel must be involved so that AI remains a tool, not a replacement. Given these developments, Albania is moving quickly in the use of AI. One of the research groups working in this direction is our group, AI4MED, part of the NanoBalkan Institute at the Academy of Sciences of Albania. Although terms like E-nurse and E-doctor may currently sound as if they come from science fiction movies, they are already becoming a reality. E-nurse will be an AI system integrated into hospitals and clinics that handles certain tasks such as initial triage, patient interviews, monitoring vitals, reminding about medication doses, flagging abnormal results, and non-urgent follow‐ups. This system would work under supervision of human healthcare workers. E-doctor will be a more advanced AI decision support system, possibly in specialties like radiology, pathology, oncology, where large data sets are used to suggest diagnoses, recommend treatment paths, or monitor progression. The human doctor would validate and lead the final decisions. For rural or underserved areas, AI chatbots or virtual assistants might manage routine care or provide health education, refer to doctors when needed, or coordinate telemedicine. AI could help with disease surveillance, predictive modelling (e.g. outbreaks), personalized prevention plans, etc.

Albania has taken a globally unprecedented step by appointing Diella as an AI minister overseeing public procurement it’s more than a symbolic gesture. It reflects a strategy to reduce corruption, ramp up efficiency, and align with EU norms. Healthcare AI is following close behind. The emergence of “e-nurse” or “e-doctor” roles seems likely over the coming years, not as stand-alone replacements of human caregivers, but as partners tools that can offload routine work, enhance decision making, and improve access.

If Albania manages to balance innovation with transparency, legal grounding, ethical oversight, and strong human engagement, it might become a model for AI governance and AI in healthcare in the region. But missteps in oversight or trust could undermine progress.

AI4MED Research Group

www.ai4med.net